A Case for the Data Center

In the data center series, we dive into all the components of a data center - from raw materials to software. Here we lay the foundations. Up next - land, energy, and physical infrastructure.

One exciting trend in venture right now is a re-found interest in the data center. Nvidia’s meteoric rise to the world’s most valuable company makes many of my older & wiser colleagues reminisce when networking giant Cisco briefly surpassed Microsoft for this title in March of 2000 - reaching a market cap of $500B ($885B in today’s dollars). Going just a little further down the dotcom rabbit hole - at the bubble’s peak in 2000, ~29% of overall deployed venture dollars were invested into semiconductors and computer networking vs. ~3% in the recent 2021 ZIRP peak.

So what happened? Did venture miss a big category? Are we entering another data center bubble?

Well for starters, in the 2010s, much of the value of the data center accrued to the hyperscalers (GCP, AWS, Azure, etc.). Enterprises were (and still are, shockingly 55% still maintain their own infrastructure on premises) too busy worrying about migrating to the cloud and digital transformation to concern themselves with how the hyperscalers ran their data centers. As these hyperscalers (GCP, AWS, Azure, etc.) grew cloud infrastructure spending to exceed overall on-premise data center hardware & software spend by 2019, they became the highly concentrated buyers of majority of data center hardware and software. As a result, they were able to commoditize the data center hardware and infrastructure market via the following mechanisms:

Standardization

The hyperscalers drove standardization of data center hardware components to ensure compatability and interoperability. One example is Meta’s Open Compute Project. Started in 2011, it promotes the sharing of data center designs and best practices and counts Microsoft, Google and Intel among its 200 member organizations. This made it challenging for data center hardware and software companies to build moats and switching costs.

In-house hardware development

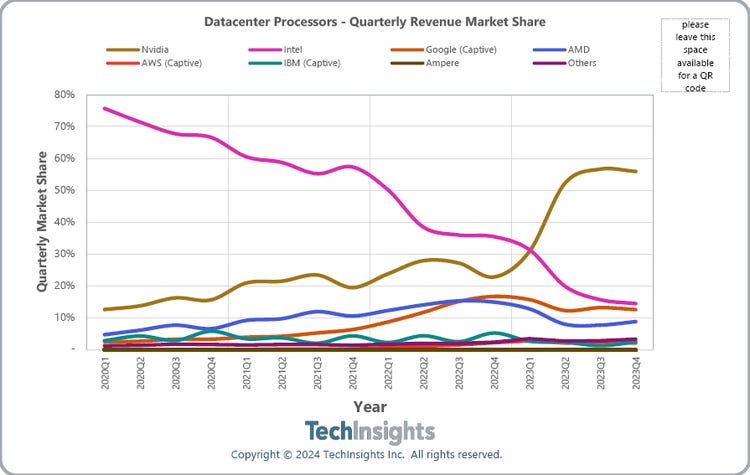

Some of the hyperscalers like Google and Amazon have developed their own hardware - including custom servers, networking equipment, and specialized processors like AWS’s Graviton and Google’s TPUs that make it difficult to compete on price. This squeezed the margins of data center hardware companies. In fact, today Google is the 3rd largest data center processor provider by market share - behind only Nvidia and Intel (and bigger than AMD).

Economies of scale

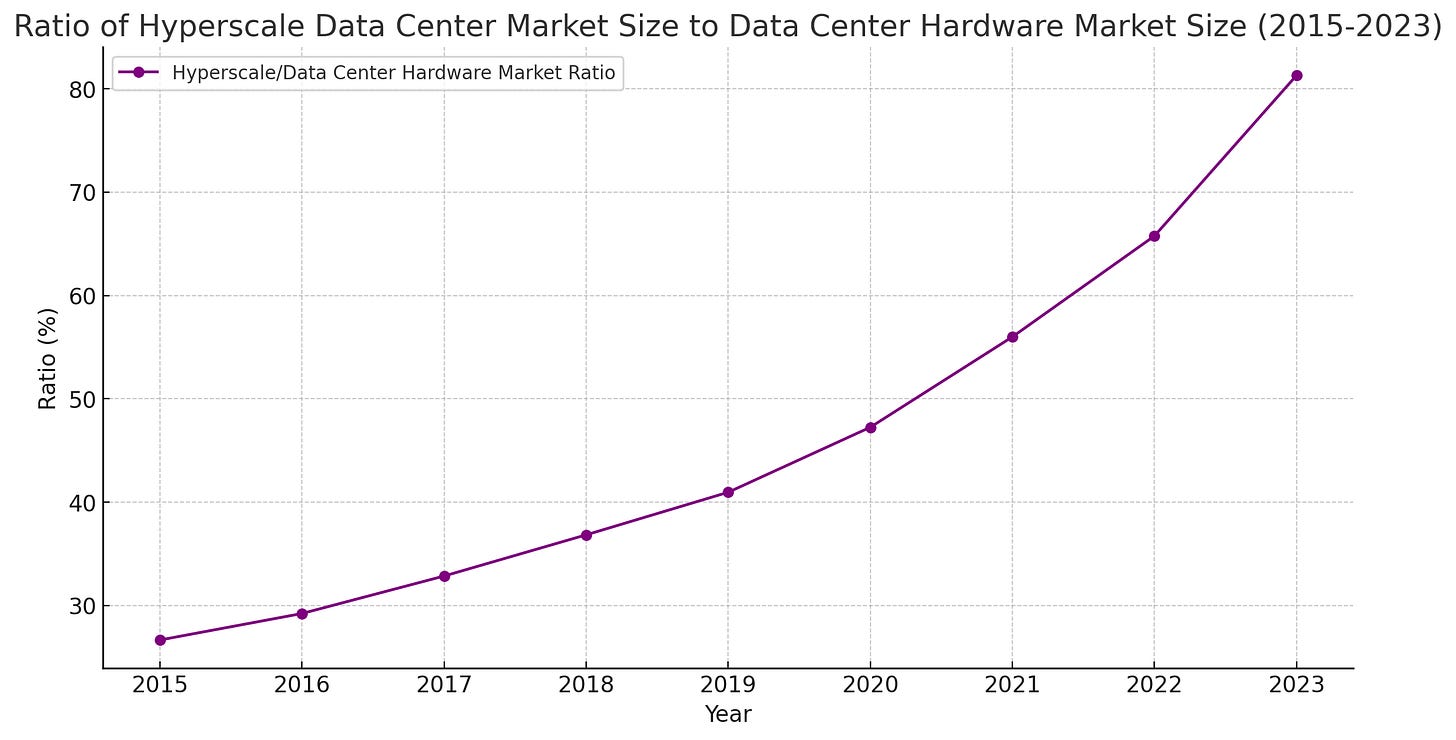

The hyperscalers’ buying power grew in proportion to their revenues. From 2015 to 2023, the ratio of hyperscale data center market to the overall datacenter hardware & infrastructure market grew from 27% to 81%. This level of customer concentration resulted in lots of buying power - further commoditizing the data center hardware and software market.

Investors were also captivated about “software eating the world” in 2011 and the resulting boom in B2B SaaS just pushed computer hardware out of the overton window. Lower CAPEX software businesses allegedly meant higher margins and faster growth resulting in higher exit multiples, less required follow-on capital, and lower dilution resulting in higher exit ownership.

The rise of the hyperscalars, the resulting commoditization of data center hardware and infrastructure, and the shift in interest to software applications sapped the data center venture market for past couple decades.

The result? A relatively consolidated industry of 191 mature public incumbents with a median 1996 founding year and average market cap of $12B (excluding Nvidia’s $3T market cap outlier) vs. 610 in enterprise SaaS with a median founding year of 2007 and and average market cap of $1.2B.

An often cited misconception is these 191 data center hardware & infrastructure companies trade at lower multiples relative to their software peers, making the space a less compelling investment category. Yet median EV/Revenue is actually higher than enterprise software (2.8x vs. 2.4x respectively). In other words, the market gives the median data center hardware & infrastructure company more of a premium over the median enterprise software company.

The premium on these public data center hardware & infrastructure companies relative to their enterprise SaaS peers is likely attributable to their comparable average growth rates (12% vs. 13% respectively) despite higher median EBITDA margins. 73% of public data center hardware & infrastructure companies are profitable vs. 49% of public enterprise software companies.

The mature state of the data center hardware & infrastructure space and competitive exit multiple comps suggests the market is ripe for disruption and that disruption is venture back-able. Industry concentration - as evidenced by 10x the average market cap of SaaS - suggests few winners but large outcomes.

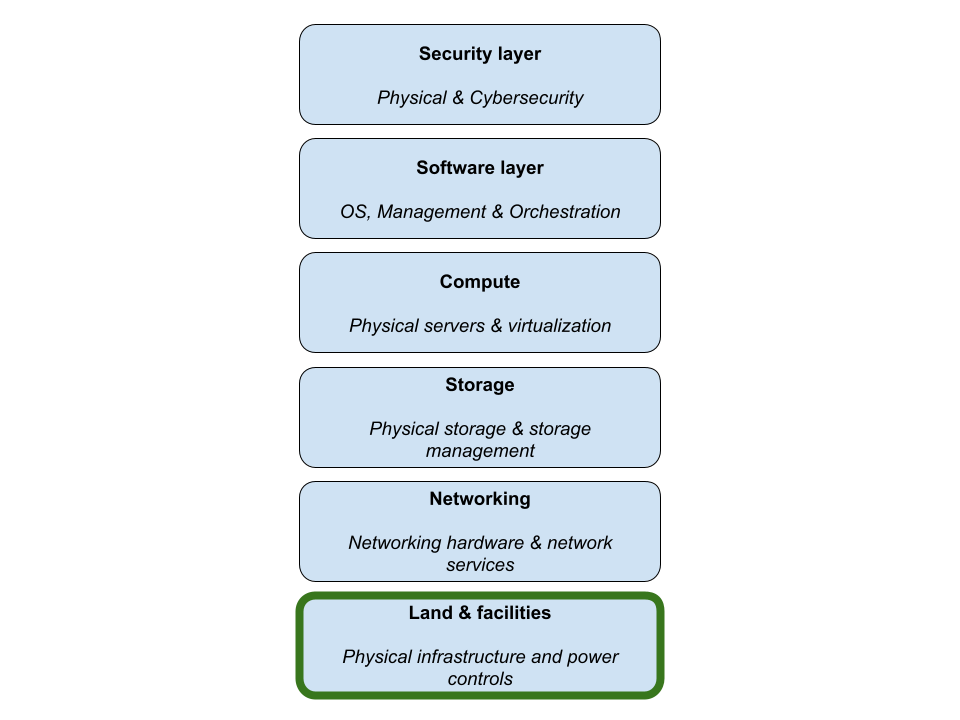

To really understand the opportunities in the data center today and identify potential exciting initial wedges for these future winners, we must examine each layer of the data center stack, shown below, in detail:

In the next installment to this data center series, we will deep dive into land & facilities, discussing the physical infrastructure and energy requirements of the data center. We’ll start in 1946, when the world’s first datacenter - the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC for short) - opened its terminal in a modest 1800 square foot room at the University of Pennsylvania. From there, we’ll work up the stack in subsequent installments of this series.